Women graduates, 1920s.

Singled Out

How Two Million Women Survived Without Men after the First World War

To the Bridget Jones generation it often seems as if available men are getting scarcer; but there is nothing new about young women who can’t find relationships.

Singled Out tells the story of a generation of women, brought up in the unquestioning belief that marriage was their birthright, who discovered after the 1914-18 war that there were, quite simply, not enough men to go round. In the 1920s they were known as the ‘Surplus Women’.

This book is a rich, moving and ultimately affirmative account of the spinsters forgotten by history but remembered by many of us as our teachers and our maiden aunts. Grief and war forced these women to rebuild their lives, and to stop depending on men for their income, identity and happiness. Drawing on a wealth of sources including unpublished autobiographies, individual interviews, problem pages and lonely hearts columns, it explores their economic, emotional and sexual survival.

Singled Out vividly describes the deprivations: frustration, poverty, childlessness; but also demonstrates the rewards: profound friendships, professional fulfilment, independence. Reincarnated from her origins as the warped and unhinged old maid of Dickensian fiction, the single woman emerges from the 19th Century shadows and finds a new role teaching, nursing, campaigning, earning her own living, and in certain circles acquiring an enviable sexual glamour. From mill girl to model, secretary to scientist, poet to professor, here is a ‘magnificent regiment’ of unsung women who made themselves indispensable and changed their century.

For many of the ‘Surplus Two Million’, being denied marriage was a liberation and a launching pad. Thanks to them, in the twenty-first century, women feel empowered by history to expect the equality, respect and rights accorded to them by law and justice. Through sheer force of numbers, they steered women’s concerns to the top of the agenda, and there they have remained.

I am available to promote Singled Out through appearances, interviews and articles.

For further information contact Amelia Fairney at Penguin amelia.fairney@uk.penguingroup.com

Excerpts from Singled Out:

Excerpt 1

from Chapter 1 “Where Have all the Young Men Gone?”

Philip and May had been playmates from the age of six. He was a city boy from Manchester, the son of middle class business people, but May got to know him because he would come to stay with his aunt in the village in the summer holidays. Little by little Philip and May became close, and after his return home he would cycle the twenty miles from Manchester to spend time with her on her afternoons off.

“It was love’s young dream… We walked for miles through fields, woods and country lanes…”. Philip loved to talk to her about his passions. Out of the small amount of money he had, he would buy her postcard reproductions of famous pictures. The little images delighted her. One of these above all seemed to sum up the happy prospect that awaited the young lovers – a landscape entitled ‘June in the Austrian Tyrol’. They would pore over it together, seeing in the picturesque setting an enchanted future. ‘I love that picture too,’ whispered Philip. ‘So – when I am through with Cambridge and in a post, we will get married and go there for our honeymoon.’

Philip and May had been courting for nearly five years when the First World War broke out. As a Quaker Philip believed firmly in the principle, ‘Thou shalt not kill.’ He registered as a pacifist, nevertheless he was imprisoned. In prison he studied first aid and care of the wounded, and on his release, felt impelled to put these skills to use. Promptly, he volunteered for active service in France as a stretcher bearer.

May waited anxiously and patiently for his safe return. She treasured the brief letters he was able to send her – sometimes only a printed card on which he had ticked the box beside, ‘I am well’. At last came a letter saying he was due for leave. May was walking on air.

More than sixty years later, when she wrote her memoir, Miss Margaret Jones barely faltered in the telling of what happened next, but she didn’t dwell on the details. Probably the old lady was still too pained by her memories to write more than a few sentences:

Tending graves at Abbeville, France, 1918

“Then everything was shattered; a letter came from the War Office to say he had been killed in action. The shock and loss was terrible, I felt I had lost half of myself, or was it my twin soul. I knew then that I should die an old maid.”

Miss Jones re-read what she had written, and added the next words in a light pencil script:

“I was only twenty years old.”

After Philip’s death the impulse to continue the account of her memories leaves her. We know no more, for ‘My Love Story’ simply ends there, with the rest of the page left blank.

Excerpt 2

from Chapter 5 “Caring, Sharing...”

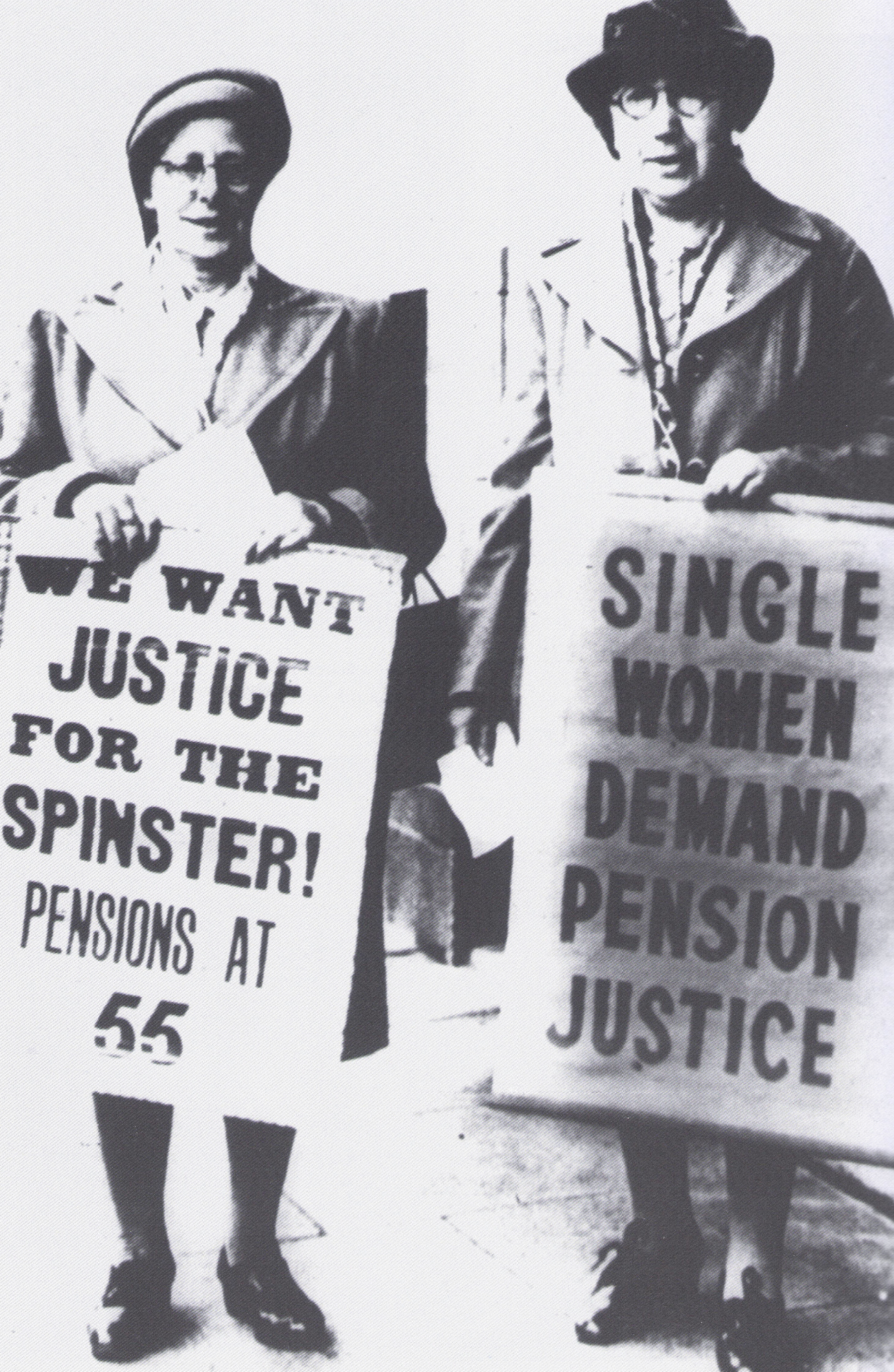

Florence White had a mission. In April 1935 she set up the National Spinsters Pensions Association to fight for the right to pensions of unmarried working women. And she struck a chord: six hundred women attended the first meeting of the NSPA; four months later nearly eight thousand had joined, and by December the Association had sixteen branches spread across the north of England. Florence, who was now nearly fifty years old, had found her life’s work, and it was full-time. She was determined to make the nation ‘spinster conscious’.

Campaigning for spinsters: on the right, Florence White

In 1929 Florence and her sister Annie opened a confectioner’s and baker’s in Lidget Green. Annie baked the cakes and ran the business. Not only that, she turned her literary talent to writing Florence’s speeches and acted as her secretary. Every day, while Annie toiled in the bake house, Florence was out on the campaign trail – Manchester, Stockport, Leeds, Leicester. Her return was an anxious moment at the Lidget Green shop. Rows between the sisters erupted with terrifying frequency, and Annie could give as good as she got. If you walked into the middle of one you took the consequences.

But Annie was always there for her sister. She was secretary, editor, speech-writer, companion, political hostess, cook, home-maker. Neither ever considered for a moment leaving the other; neither doubted the other’s worth. Through triumphs and crises they were shoulder to shoulder, working to the same end. The things that mattered to them were taken for granted, unspoken and unquestioned, as such things are in families - their cat Ginger for instance. During the Second World War the White sisters offered refuge to a spinster who had been evacuated from Bethnal Green. This lady had the misfortune to step backwards off a chair and accidentally land on Ginger. Sadly there was no hope for the cat, who had suffered internal injuries. Both the sisters were prostrated with grief. ‘Auntie Florence was crying for days,’ remembered their niece. ‘We dared not mention his name for weeks and his collar had to be kept safely in a drawer.’

In 1940 Florence White’s campaign bore fruit. Insured spinsters over sixty would get ten shillings a week. It was not as good as she had hoped for, and she was to continue fighting for a better deal, but it was a major concession by the government, and a personal triumph. The tributes poured in from her supporters. In the words of a Bradford factory worker: ‘All the spinsters in England should rise today and salute her’. And the following couplets were sent in from a schoolchild admirer:

God made each maid a husband

But men on earth must fight,

So just in case there aren’t enough

He made Miss Florence White.

Gallery

Reviews

Selina Hastings, Sunday Telegraph

“Remarkably perceptive and well-researched… Nicholson is the author of that brilliantly original study Among the Bohemians, and in Singled Out she has produced another extraordinarily interesting work, sensitive, intelligent and well-written”

•

John Carey, The Sunday Times

“Pioneering, powerful, inspiring…”

•

Frances Spalding, Daily Mail

“Virginia Nicholson’s method is sympathetic. She does not browbeat us with statistics and social trends, but instead tells us stories about individual lives… [she] has a light but knowing touch… A ground-breaking book, richly nuanced with titbits of information, insight and understanding”

•

The Economist

“The charm of Singled Out lies not so much in its uplift as in its method and atmosphere… The period is beautifully caught… Inspiring, lovingly researched, well-written and humane. Virginia Nicholson has found one of those subjects which sits unregarded under our noses and has discovered in it a rich seam of personal and historical interest”

•

Hilary Spurling, the Observer

“It is high time to dig [this generation] up again, salute their memory and listen to their sad and uncomplaining voices unmuffled at last in Nicholson’s brave, humane and honest book.”

•

Lucy Lethbridge, New Statesman

“Singled Out is a celebration of pluckiness, realism, intellectual independence and self-reliance. Nicholson has taken a feature of 20th Century British social life that is familiar to us – but here gives it the intelligent and humane examination it deserves.”

•

Jane Ridley, Literary Review

“Virginia Nicholson has found a wonderful subject. The virtue of her book is that she doesn’t attempt to generalize or theorise or preach, but allows the women to speak for themselves. Taking the life stories of a sample of women, she skillfully weaves them into her narrative, and the result is not an arid social history but a book packed with human interest, elegant, funny and a compelling read”

•

Rosemary Goring, The Herald

“Nicholson has done a sterling duty in revealing the degree of fortitude and even humour with which this ill-fated but gallant sisterhood conducted themselves. Theirs is a story of quiet bravery worthy of the men they lost in battle.”